BRUSSELS — In an historic ruling aimed at limiting online piracy, the European Court of Justice ruled on March 27 that Internet service providers in the EU can be ordered to block access to websites that infringe on copyrights.

The Court of Justice — competent to judge the validity of an EU law or give indications on how to interpret it — had been asked to rule on a case referred to it by the Austrian Supreme Court. In the case, two film companies — one German, one Austrian — had become aware that their films could be viewed and downloaded from the website Kino.to without their consent.

Basing their arguments on the EU Copyright Directive, the two film companies successfully requested that an Austrian court prohibit the Internet service provider (ISP) concerned — UPC Telekabel — from providing its customers with access to Kino.to. Seeking legal confirmation for such a ruling, the Austrian judges also referred the matter to the Court of Justice.

The Court of Justice duly upheld the Austrian court’s decision. An ISP, the Court of Justice ruled, may be asked to block access to a website that allows its customers to view and download copyrighted films and music. This ruling has set a precedent in defining the role of ISPs in the fight against online piracy.

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, a music industry lobby group, welcomed the ruling, saying it confirmed that “website blocking is consistent with fundamental rights under EU law” and that “copyright is itself a fundamental right requiring protection.”

Artists argue that they need to be compensated for their work, which has prompted them to call for greater intellectual property right protection. To make a living, they emphasize, they need their copyright revenues in addition to the money they make from composer rights and concerts.

Not all artists are opposed to free downloads, though. Vasilis Panagiotopoulos, a Brussels-based artist manager, argues that for lesser-known artists, illegal downloads can be a boon. For smaller bands, he says, “it is in their interest to get their tracks out there.”

Others, like David Byrne, maintain that the real issue is that the biggest slice of the pie goes to the music industry, not the artists.

Natural downloading

On the other hand, a generation of Internet users grew up with the idea that downloading music and films from the Internet is normal and natural. They are often not even aware that this is illegal because the songs and the films are protected by copyrights.

In recent years, this highly complex issue has moved up on the political agenda, with some EU countries adopting national laws seeking to reduce Internet piracy, such as downloading and exchanging songs and films and software without respecting copyrights rules.

The United Kingdom and Ireland, for example, are among a handful of countries already taking action to block access to sites such as the Swedish-based file-sharing site The Pirate Bay.

The toughest stance, though, has been adopted by France. Under the Hadopi law, the country set up a new authority to monitor web access and prevent illegal file-sharing, with sanctions such as fines or cutting off the Internet access of those violating the law.

At the other extreme is the Swedish Pirate Party, a single-issue political party focused on preventing limitations to free downloading. During the last elections of the European Parliament, in 2009, the Pirate Party won over 7 percent of the vote, thereby electing two members to the current European Parliament. A year later, the Pirate Party International was founded in Brussels. It defines itself as the political incarnation of the freedom of expression movement.

The controversy is not limited to Europe, however. In the United States, a heated debate regarding online privacy law emerged in 2011 with the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA). Both bills were designed to tackle online piracy, with particular emphasis on illegal copies of films and other forms of media hosted on foreign servers. They proposed that anyone found guilty of streaming copyrighted content without permission 10 or more times within six months should face up to five years in jail.

SOPA and PIPA raised concerns among businesses, as they could foresee websites being shut down for allegedly encouraging piracy. Ordinary citizens were also concerned that the legislation would give government bodies the right to request personal data on suspects without any legal protection. In January 2012, both the Senate and the House of Representatives decided to postpone consideration of the legislation until there was wider agreement on a solution.

The paradox is that the two American bills also raised concerns with the Europeans about its potential consequences on Europe. Marietje Schaake, a Dutch MEP appointed to draw up a report on Internet freedom globally, led a campaign to get the bills amended. In December 2011, she wrote a letter to the U.S. Congress stating that the bills would be “detrimental to internet [sic] freedom, internet [sic] as a driver for economic growth and for fundamental rights, not only in the EU, but globally.”

Copyright protections vs. privacy

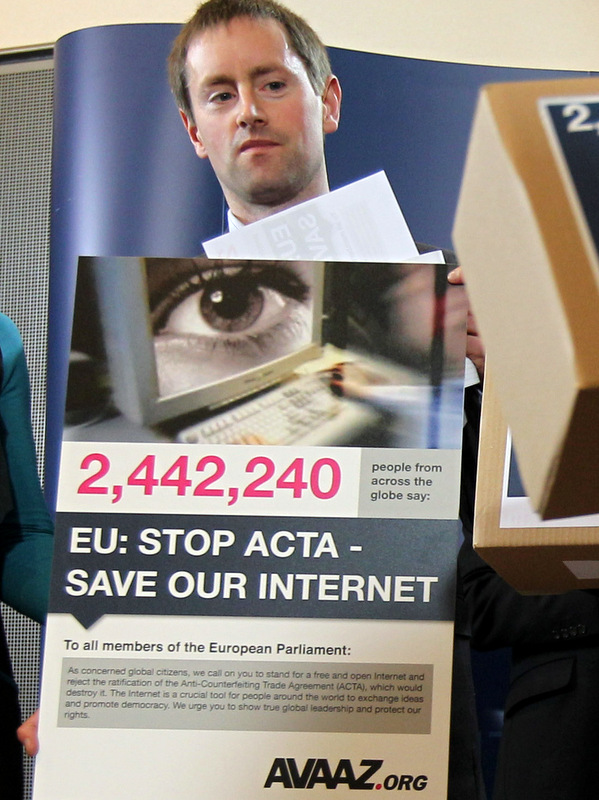

Additionally, in July 2012, the European Parliament rejected the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), an international treaty whose stated aim was to enhance international cooperation in the fight against intellectual property rights infringements, including online trafficking in copyrighted material.

The parliament was concerned that free downloads of movies and music might lead to prison sentences if ACTA were ratified. They also feared that exchanging material on the Internet may become a crime and said the accord would allow for massive online surveillance.

Similarly, in an opinion on ACTA, the European Data Protection Supervisor — an independent supervisory authority devoted to protecting personal data and privacy in the EU institutions — ruled in 2012 that “many of the measures would involve the large scale monitoring of users’ behavior and of their electronic communications. These measures are highly intrusive to the private sphere of individuals and, if not implemented properly, may therefore interfere with their rights and freedoms to, inter alia, privacy, data protection and the confidentiality of their communications.”

In other words, while not disputing the need to regulate movie and music downloading, both the European Parliament and the European Data Protection Supervisor thought this need did not justify enacting measures with the potential to intrude on individuals’ privacy and interfere with their rights and freedoms.

These concerns now seem to be negated by the Court of Justice. The court’s latest ruling marks an about-face from two precedent rulings, in which it had opposed a policing role for ISPs.

Indeed, in 2011, the Court of Justice issued a ruling establishing that EU member states cannot impose Internet filtering for the purpose of preventing illegal downloads of copyrighted files because such an injunction “does not comply with the requirement to strike a fair balance between, on the one hand, the right to intellectual property, and, on the other, the freedom to conduct business, the right to protection of personal data and the freedom to receive or impart information.”

The ruling was reinforced in February 2012, when the Court stated that online social networks cannot be forced to block users from downloading content illegally, as this would increase their costs and infringe on users’ privacy.

The latest ruling by the Court of Justice begs some questions: What happened to all of the court’s previous concerns? Why does intellectual property right protection now seem more important than the right to privacy?