A crisis continues to unfold in the United States’ prisons, where the prison population is vastly disproportionate to the country’s general population demographics. Per 2013 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, blacks represented 13.2 percent of the U.S. population, yet, according to the Sentencing Project, blacks represented 38 percent of all individuals in federal or state prisons, as of 2011.

A crisis continues to unfold in the United States’ prisons, where the prison population is vastly disproportionate to the country’s general population demographics. Per 2013 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, blacks represented 13.2 percent of the U.S. population, yet, according to the Sentencing Project, blacks represented 38 percent of all individuals in federal or state prisons, as of 2011.

This imbalance has manifest at a time when for-profit prisons are posting record profits and announcing their expansion into other segments of the post-judicial corrections portfolio. For example, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, Corrections Corporation of America — the nation’s largest for-profit prison operator — has responded to calls coming from some states regarding the high cost of long-term housing of inmates by announcing expansions of the company’s prison rehabilitation, drug counseling and prisoner re-entry programs.

This diversification has created the impression that the CCA is not only seeking to be the primary jailer in many states, but is also seeking to offer the alternative to incarceration in these communities. In light of the CCA’s and other for-profit prison operators’ heavy political lobbying and the private prison industry’s record for having a higher racially disproportionate population than what exists in comparable public prisons, there is reason to believe that CCA and other for-profit prison operators are succeeding in “gaming the system.”

“What CCA is doing is vertically-integrating,” said Charles Gallagher, chair of the sociology and criminology department at La Salle University, to MintPress News. “The for-profit prison population has increased recently, so there is little need for the for-profit prison providers to hedge against losses. What the for-profits are doing is trying to corner the after-prison market — the halfway houses, the drug treatment centers, etc. — with the understanding that if they were to enter this market, they would likely end up controlling it.”

While there is evidence to suggest that the growth in non-violent crime apprehension and sentencing is a component of both the race disparity in prisons and the profit spike among for-profit prisons, there may be a more prominent explanation of why there are so many blacks and Latinos in the prison system today.

The school-to-prison pipeline

In the years since the Columbine High School Massacre, in which two high school students — Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold — killed 13 students and teachers and injured 21 others at Columbine High School in Columbine, Colorado, schools have increasingly taken a “zero-tolerance” approach to in-school disruptions. While this approach may help ease parents’ concerns about a school’s safety, the realities of these policies cast a troubling image.

In 2009, for example, the Los Angeles Unified School District reported that among its students who were given out-of-school suspensions, 62 percent were Hispanic and 33 percent were black. Only 3 percent were white. Similarly, the West Valley School District in Spokane, Washington, reported that of the students who were expelled that year, 20 percent were black and 60 percent were white — this, for a school district whose student body is 86 percent white and 4 percent black.

Also in 2009, in the Normandy School District of St. Louis, 100 percent of all students who received more than one out-of-school suspension, 100 percent of all students expelled without educational services, and 100 percent of all students referred to law enforcement were black. In New Orleans, all of the Orleans Parish School Board’s expulsions under its “zero-tolerance” policy were black, as were 67 percent of the board’s school-related arrests. New Orleans’ RSD-Algiers Charter School Association reported that black students made up 75 percent of students expelled without educational services, 100 percent of expulsions under a “zero-tolerance” policy, and 100 percent of school-related arrests.

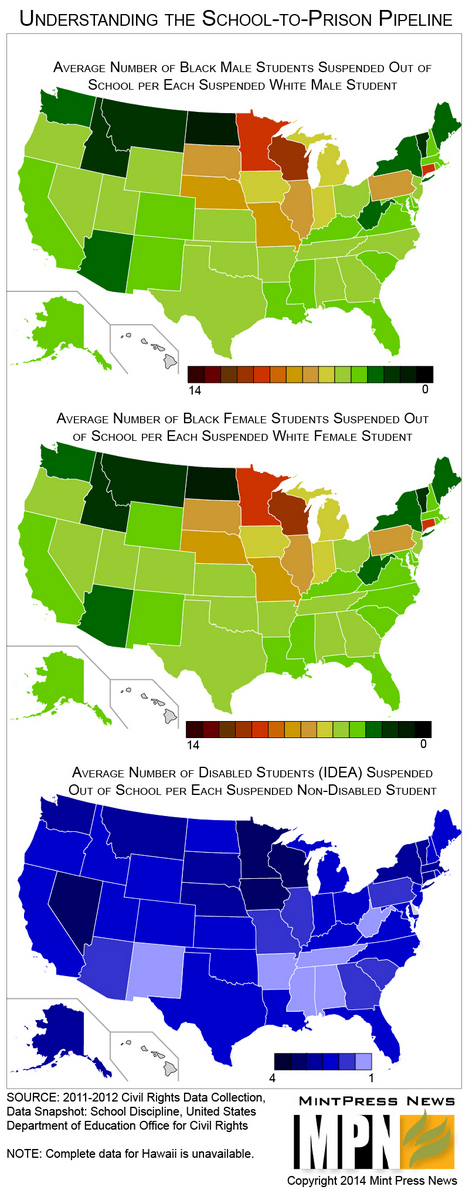

These examples, however, are far from unusual. According to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, no state — on average — has suspension rates that show white students being punished at a rate on par with the suspension rate for black students (see Figure 1). While New Jersey, New York and North Dakota reported rates below the national average — three black males suspended per every white male suspended, six black females suspended per every white female suspended — the most equitable state reported, New York, still had a rate of 2 black males suspended per every suspended white male. Wisconsin, the most inequitable state listed, reported a black-to-white suspension rate of 8 to 1 for males and 10.5 to 1 for females.

Similarly, black students constitute only 16 percent of the nationwide student population, but they comprise 27 percent of students referred to law enforcement and 31 percent of students subjected to school-related arrest. White students, meanwhile, make up 51 percent of the national student body, 41 percent of the students referred to law enforcement, and 39 percent of those arrested.

This disparity is commonly known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” and is thought to be the major driver of the disparity in black incarceration rates in the state and federal prison systems. When a student is referred to law enforcement, he or she becomes part of the judicial system — he or she receives a police and/or court record that may or may not be sealed; he or she is potentially exposed to incarceration; and his or her family is subjected to fines and court fees that the family may be unable to pay.

The referral also “marks” the student. Even if the student receives no jail time as a result of the referral, the referral itself suggests to law enforcement and to school officials that the student is a potential troublemaker, prompting heightened scrutiny of the student’s actions both in and out of school. This may also increase the likelihood of that student being rearrested, removed from school and placed in alternative education programs, or expelled. It could also increase the likelihood of that student dropping out of school altogether.

“We know now that some kids are being suspended disproportionately compared to other kids,” Jody Owens, the managing attorney for the Mississippi office of the Southern Poverty Law Center, told MintPress. “We also know that this disparity between school punishment between these targeted kids and their white counterparts for the same offenses is at an alarmingly high rate. This disparity is causing a large number of these kids to be introduced to the juvenile justice system, which is the first stop on a long slide toward eventual placement in the adult prison system.”

Why the pipeline exists

No one is sure why the “school-to-prison” pipeline exists. One theory ties it back to the for-profit prison system. It has been recognized that it costs less to house a minority in a for-profit prison than it is to house a white prisoner. The reason for this is age; the average white prisoner is significantly older than the average black or Latino prisoner. This means that the health costs for a black or Latino prisoner would be less than that of a white prisoner. As there is a higher profit motive for housing black and Latino prisoners, it follows that for-profit prisons would lobby for laws and policies which encourage the detention of young minority offenders.

This was the case in the “kids for cash” scandal in which two Luzerne County Court of Common Pleas judges in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, were accused of accepting kickbacks from the developers of two for-profit juvenile detention facilities for their support toward receiving the county’s contracts and for imposing undue sentences in order to increase the number of inmates in the detention centers. Detainees were sentenced to incarceration for charges as petty as mocking a principal on MySpace, trespassing in a vacant building and shoplifting DVDs from Wal-Mart.

Another theory is that as the students most likely to be suspended are underachieving students who, due to a lack of resources or parental involvement at home, are unlikely to perform well on standardized achievement tests, school officials knowingly and excessively refer these students to law enforcement. An arrest gives the school officials justification to remove the low-performing student from the school, which improves the school’s potential for a strong show in academic performance tests, such as the Common Core assessments. This would lead to an increase in state and federal funding, which the school can use to make up for austerity cuts due to the “Great Recession.”

A third theory states that the problem involves “over-policing” on the part of law enforcement. This notion posits that a police officer or police department will eventually grow “hardened” upon having to respond to repeat school referrals for non-white students. The police will eventually start to see all non-white youth as potential criminals — both on school grounds and in everyday society, thus leading to a permanent aggressive attitude and responses that tend to be based on statistics rather than on the actual needs of the community.

Moreover, this theory is a reflection of the “broken-window” theory, in which police are expected to respond to even the slightest infraction, such as a broken window, as ignoring it could contribute to a sense that no one cares. This notion of indifference, then, might lead to larger infractions, like vandalism or violence. As seen with the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and with the New York Police Department’s use of “stop & frisk,” this approach can make it seem as if police are needlessly overbearing or militaristic, even if their intentions are arguably benign.

The most likely theory, however, is that many low-income school districts and communities lack the financial resources to implement alternative education programs and provide community intervention. According to the Sentencing Project, studies have found that intervention programs can have a tremendous effect. For instance, the Prenatal/Early Infancy Project, of Elmira, New York, in which a nurse makes 20 home visits during a pregnant teen’s prenatal period and during the first two years of the resultant child’s life, was found to significantly reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect. Further, the arrest rates decreased for both the mothers and children who participated in the program.

Programs such as the Prenatal/Early Infancy Project and the High/Scope Perry Preschool Project — which tracked the short- and long-term effects of preschool programs such as Head Start — show that behavior patterns are established early in life. Children who come from a stable environment, who have access to the resources needed to thrive, and who are given early access to education are less likely to be socially disruptive later. The RAND Corporation has found that every dollar invested in preschool education produces $7.14 in societal savings.

This lack of funding also plays a role in the suspension rates of disabled students and non-disabled students (see Figure 1). Many low-budget schools do not have the resources to train staff on how to handle special needs students — as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act — or toward offering special programs for students with behavioral problems or other special needs students. This leaves these schools to refer special needs students to law enforcement or remove them from classes, thus endangering the lifetime learning capability of these students who are already on the fringe.

“If you go into the suburbs of most big cities, which are typically white, there are few problems with their school budgets; their tax base is sound,” said Gallagher, the criminology and sociology chair at La Salle University. “In the school my kids attend outside of Philadelphia, for example, only 2 percent of the students are on free-or-reduced lunches. One mile away in the city, the reverse is true. This suggests poverty and it suggests that for such schools, a host of other poverty-related issues are coming into the classroom with the student.

“This is a vestige of racism. Wealthy communities have wealthy schools, so that those born to money have exclusive access to the resources and education needed to go to college and make money. Those outside of these communities must do without.”

Moving forward

The Southern Poverty Law Center’s Owens believes that all four of the above mentioned theories contribute equally to the “school-to-prison” pipeline and all four must be addressed in order to solve it.

“I personally believe that the police are doing the hardest job in the world — the enforcement and insurance of the public safety — and that the ranks of the police are filled with hard-working, responsible men and women,” he said. “But, this does not mean that we should or can ignore the fact that ‘white privilege’ exists and has been manifest in the way schools are dealing with its black and brown students.”

Owens argues that the first step toward moving forward is to have an honest conversation about the realities of the current situation. For example, it is crucial to acknowledge that frequently arresting young black students encourages the “over-policing” of young black men on the streets. It must be recognized that perceptions and biases against young people of color may have set in and that these need to be met with training and awareness education. Additionally, communities must play a significant role in pushing for the societal and policing changes needed to shut down the “school-to-prison” pipeline.

Marsha Levick is chief counsel and deputy director for the Juvenile Law Center. In conversation with MintPress, she argued that there is evidence of progress being made to remedy the “school-to-prison” pipeline. In one example she pointed to, the Los Angeles Unified School District has introduced discipline policies that require school administrators to be cognizant of the number of Latino and black students they discipline or refer to the judicial system and act accordingly toward being more proportionate to the school’s demographics.

“There’s a robust conversation going on throughout the nation discussing the incarceration of men and boys of color,” said Levick. “I honestly believe that there is an effort to move forward and to correct this situation, and in some jurisdictions, there has been significant movement toward addressing racial bias and toward correcting patterns of ‘over-policing.’

“This, however, has not manifest into a national tide of change, but there is hope that these small glimpses into examples of where things went grossly wrong, such as Ferguson and the Los Angeles Unified School District, can bear light to the underlying problem and may lead to lasting solutions.”